Advocacy and Community Reconciliation: The Long View of Transition

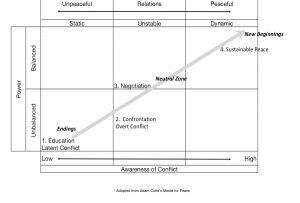

The purpose of this overview is to outline the key role that advocacy plays in community reconciliation and the long view of transitions in large-scale social change efforts. The following is an effort to overlay Adam Curle’s work in the early 70s and William Bridges’ Transitions Framework. This matrix (see below) will be helpful in plotting where we are in a given community reconciliation project and for suggesting potential activities we might choose to undertake at a given time or in a particular point of transition. At least three key peacemaking functions identified in this progression toward change are education, advocacy and dialogue. The importance of these three functions can not be understated, each emerge as crucial in a typical path of conflict engagement and each play a crucial role in the effort toward community reconciliation.

The purpose of this overview is to outline the key role that advocacy plays in community reconciliation and the long view of transitions in large-scale social change efforts. The following is an effort to overlay Adam Curle’s work in the early 70s and William Bridges’ Transitions Framework. This matrix (see below) will be helpful in plotting where we are in a given community reconciliation project and for suggesting potential activities we might choose to undertake at a given time or in a particular point of transition. At least three key peacemaking functions identified in this progression toward change are education, advocacy and dialogue. The importance of these three functions can not be understated, each emerge as crucial in a typical path of conflict engagement and each play a crucial role in the effort toward community reconciliation.

To begin, a brief overview of William Bridge’s Transitions Model:

- Phase 1 – Endings – The beginning of a transition is not the outcome but the ending that one will have to make to leave an old situation behind. The psychological transition that humans often experience when situations change around them depends on letting go of the old reality and the old identity of oneself before the change can take place (Bridges 1991). Once a person has let go of something, the transition begins. After this, the second step, the neutral zone occurs.

- Phase 2 – Neutral Zone – “This is the no-man’s land between the old reality and the new. It is the limbo between the old sense of identity and the new (Bridges 1991: 5).” This is the most important phase to understand in that if a person does not expect it and understand why it is there, he is likely to rush through it and be discouraged when he cannot do so. One is apt to believe that the confusion she feels is a sign that something is wrong with her (Bridges 1991). A second reaction to the neutral zone might be the desire to escape it or abandon the situation. Another possibility is the loss of a great opportunity if one escapes the neutral zone too early. Bridges states, “Painful though it often is, the neutral zone is the individuals and the organization’s [community’s] best chance for creativity, renewal, and development (1991: 5).” Thus the neutral zone, as the core of the transition process, is both dangerous and full of opportunity.

- Phase 3 – New Beginnings – The final phase of the transition is the new beginning. “The beginning took place only after they had come through the wilderness and were ready to make the emotional commitment to do things the new way and see themselves as new people (Bridges 1991: 50).” These new beginnings require new understandings, values, attitudes and identities. Bridges argues that you cannot force a new beginning but that it is possible to cultivate, encourage and allow this final phase to occur. To make a new beginning people need: purpose, a picture, a plan and a part to play (50). “Successful new beginnings are based on clear and appropriate purpose. Without one, there may be lots of starts but no real beginnings. Without a beginning, the transition is incomplete. And without transition, the “change” changes nothing (Bridges 1991: 55).”

According to Curle, education, or “conscientization”, is needed when the conflict is hidden or covert and people are unaware of the imbalances and injustices. This unawareness can include latent conflicts that lie right under the surface of our society including long time policies that favor one group of people over another. This phase is aimed at education and raising awareness as to the nature of unequal relationships, the consequences of these systematic discriminatory practices and the need for addressing and restoring equity. This educational campaign must been done from the lens of those experiencing the injustices. This work most often occurs in the Endings phase, though ‘conscientization’ and education is an on-going process that will continue into the neutral zone and through new beginnings.

Increased awareness of issues, needs and interests leads to demands for changing the situation. Those who have been a part of the process enter the Neutral Zone while the majority remains in Pre-Endings. Such demands are rarely attained immediately, and more likely, are not even heard nor taken seriously by those benefiting from the situation. This ‘privilege’ group prefers to keep things as they are. Hence, the entry and necessity of community organizers, who work with and support those pursuing change. Their work pushes for a balancing of power, that is, recognition of mutual dependence increasing the voice of the less powerful and legitimation of their concerns present and past. This happens through some form of confronting the injustice including but not limited to truth seeking processes, campaigns, tribunals and large-scale participatory community reconciliation projects. A tremendous amount of organizing and education based work precedes these processes. Being a part of these processes can help people to acknowledge Endings and are crucial to helping communities successfully navigate the Neutral Zone.

Successful community reconciliation projects lead to an acknowledgement of the need to restructure relationships and begin the process of addressing oppression and its impact. This can result in what is increased justice and in some cases more peaceful relations. Clearly, this is not necessarily a linear process and at any point along the path, the group can jump from one quadrant to another and cycle back through the phases of transition (see overlay of the models below). For our purposes of putting onto paper a rather complex process of community reconciliation each one as unique as its context, we are attempting to lay out a long-term view of transitions that take within these conflict – one that contemplates both a vision of where we are going and a multiplicity of activities to get us there.

The overlay of these frameworks between the 3 phases of Transitions and education, advocacy and encounter/dialogue share the goal of lasting social change and restructuring unjust/conflicting relationships. They encompass the vision for justice with substantive and procedural change through genuine engagement. When justice ceases to be the goal, any particular role, activity or strategy must be questioned. While meant to be descriptive, the underlying assumption in our work is value orientation in favor of less powerful groups attaining a voice in confronting injustice and the process of restructuring.

It is crucial to note that these efforts are not mutually exclusive in that they overlap, complement and are dependent on each other. Dialogue or genuine engagement is possible when the needs and interests of all those involved and affected by the conflict are legitimated and articulated. This often happens in the advocacy (and confrontation) phase when awareness of basic needs and interests is often articulated. And to take this a step further, increased equality and justice does not often emanate from confrontation and therefore creating that space for dialogue facilitates the articulation of legitimate needs and interests of all concerned into fair, practical and mutually beneficial visions for the future.

Advocacy, for example, chooses to stand by one side for justice’s sake. Community reconciliation chooses to stand in connection to all side for justice’s sake. This lens suggests that the longer-term progress of conflict toward increased justice and peaceful relations must integrate and view these activities as necessary and mutually interdependent in the pursuit of social change and transformation.

Adam Curle and Ma’ire A. Dugan.”Peacemaking: Stages and Sequence,” Peace and Change, Vol. 8, (Summer 1982) 19-28.

Bridges, William. Managing Transitions

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!